Coordinates:  13°N 122°E

13°N 122°E

| Republic of the Philippines

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Capital |

Manilaa

14°35′N 120°58′E 14°35′N 120°58′E |

| Largest city |

Quezon City

14°38′N 121°02′E 14°38′N 121°02′E |

| Official languages |

|

| Recognized regional languages |

|

| National language |

Filipino |

| Optional languagesb |

|

| Ethnic groups(2010) |

|

| Religion |

|

| Demonym |

Filipino (masculine or neutral)

Filipina (feminine)

Pinoy (colloquial masculine)

Pinay (colloquial feminine)

Philippine (English) |

| Government |

Unitary presidentialconstitutional republic |

|

|

Rodrigo Duterte |

|

|

Leni Robredo |

|

|

Aquilino Pimentel III |

|

|

Pantaleon Alvarez |

|

|

Maria Lourdes Sereno |

| Legislature |

Congress |

|

|

Senate |

|

|

House of Representatives |

| Formation of the republic e |

|

|

June 12, 1898 |

|

|

December 10, 1898 |

|

|

January 21, 1899 |

|

|

March 24, 1934 |

|

|

May 14, 1935 |

|

|

July 4, 1946 |

|

|

February 2, 1987 |

| Area |

|

• Total

|

300,000 km2(120,000 sq mi) (72nd) |

|

• Water (%)

|

0.61[5] (inland waters) |

|

|

298,170 km2

115,120 sq mi |

| Population |

|

• 2015 census

|

100,981,437[6] (13th) |

|

• Density

|

336.6/km2 (871.8/sq mi) (37th) |

| GDP (PPP) |

2017 estimate |

|

• Total

|

$873.966 billion[7] (29th) |

|

• Per capita

|

$8,223[7] (118th) |

| GDP (nominal) |

2017 estimate |

|

• Total

|

$348.593 billion[7] (36th) |

|

• Per capita

|

$3,280[7] (104th) |

| Gini (2012) |

43.0[8]

medium · 44th |

| HDI (2015) |

0.682[9] 0.682[9]

medium · 116th |

| Currency |

Piso (Filipino: [ˈpiso]) (₱)(PHP) |

| Time zone |

PST (UTC+8) |

|

|

not observed (UTC+8) |

| Date format |

- mm-dd-yyyy

- dd-mm-yyyy (AD)

|

| Drives on the |

right[10] |

| Calling code |

+63 |

| ISO 3166 code |

PH |

| Internet TLD |

.ph |

|

|

- ^ While Manila proper is designated as the nation’s capital, the whole of National Capital Region (NCR) is designated as seat of government, hence the name of a region. This is because it has many national government institutions aside from Malacanang Palace and some agencies/institutions that are located within the capital city.[11]

- ^ The 1987 Philippine constitution specifies “Spanish and Arabic shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis.”[12]

- ^ Filipino revolutionaries declared independencefrom Spain on June 12, 1898, but Spain ceded the islands to the United States for $20 million in theTreaty of Paris on December 10, 1898 which eventually led to the Philippine–American War.

- ^ The United States of America recognized the independence of the Philippines on July 4, 1946, through the Treaty of Manila.[13] This date was chosen because it corresponds to the U.S.Independence Day, which was observed in the Philippines as Independence Day until May 12, 1962, when President Diosdado Macapagalissued Presidential Proclamation No. 28, shifting it to June 12, the date of Emilio Aguinaldo‘s proclamation.[14]

- ^ In accordance with article 11 of the Revolutionary Government Decree of June 23, 1898, the Malolos Congress selected a commission to draw up a draft constitution on September 17, 1898. The commission was composed of Hipólito Magsalin, Basilio Teodoro, José Albert, Joaquín González, Gregorio Araneta, Pablo Ocampo, Aguedo Velarde, Higinio Benitez,Tomás del Rosario, José Alejandrino, Alberto Barretto, José Ma. de la Viña, José Luna, Antonio Luna, Mariano Abella, Juan Manday, Felipe Calderón, Arsenio Cruz and Felipe Buencamino.[15] They were all wealthy and well educated.[16]

|

The Philippines ( ( listen); Filipino: Pilipinas [ˌpɪlɪˈpinɐs] or Filipinas[ˌfɪlɪˈpinɐs]), officially the Republic of the Philippines (Filipino: Republika ng Pilipinas), is a unitary sovereign state and island country in Southeast Asia. Situated in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of about 7,641 islands[17] that are categorized broadly under three main geographical divisions from north to south: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. The capital city of the Philippines isManila and the most populous city is Quezon City, both part of Metro Manila.[18] Bounded by the South China Sea on the west, the Philippine Sea on the east and the Celebes Sea on the southwest, the Philippines shares maritime borders with Taiwan to the north, Vietnam to the west, Palau to the east and Malaysia and Indonesia to the south.

listen); Filipino: Pilipinas [ˌpɪlɪˈpinɐs] or Filipinas[ˌfɪlɪˈpinɐs]), officially the Republic of the Philippines (Filipino: Republika ng Pilipinas), is a unitary sovereign state and island country in Southeast Asia. Situated in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of about 7,641 islands[17] that are categorized broadly under three main geographical divisions from north to south: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. The capital city of the Philippines isManila and the most populous city is Quezon City, both part of Metro Manila.[18] Bounded by the South China Sea on the west, the Philippine Sea on the east and the Celebes Sea on the southwest, the Philippines shares maritime borders with Taiwan to the north, Vietnam to the west, Palau to the east and Malaysia and Indonesia to the south.

The Philippines’ location on the Pacific Ring of Fire and close to the equator makes the Philippines prone to earthquakes and typhoons, but also endows it with abundant natural resources and some of the world’s greatest biodiversity. The Philippines has an area of 300,000 square kilometers (115,831 sq mi),[19]and a population of approximately 103 million.[20] It is the eighth-most populated country in Asia and the 12th most populated country in the world. As of 2013, approximately 10 million additional Filipinos lived overseas,[21]comprising one of the world’s largest diasporas. Multiple ethnicities and cultures are found throughout the islands. In prehistoric times, Negritos were some of the archipelago’s earliest inhabitants. They were followed bysuccessive waves of Austronesian peoples.[22] Exchanges with Chinese,Malay, Indian, and Islamic nations occurred. Then, various competing maritime states were established under the rule of Datus, Rajahs, Sultans orLakans.

The arrival of Ferdinand Magellan in Homonhon, Eastern Samar in 1521 marked the beginning of Hispanic colonization. In 1543, Spanish explorer Ruy López de Villalobos named the archipelago Las Islas Filipinas in honor ofPhilip II of Spain. With the arrival of Miguel López de Legazpi from Mexico City, in 1565, the first Hispanic settlement in the archipelago was established.[23]The Philippines became part of the Spanish Empire for more than 300 years. This resulted in Catholicism becoming the dominant religion. During this time,Manila became the western hub of the trans-Pacific trade connecting Asia withAcapulco in the Americas using Manila galleons.[24]

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, the Philippine Revolution followed in quick succession, which then spawned the short-lived First Philippine Republic, followed by the bloody Philippine–American War.[25] Aside from the period ofJapanese occupation, the United States retained sovereignty over the islands until after World War II, when the Philippines was recognized as an independent nation. Since then, the Philippines has often had a tumultuous experience with democracy, which included the overthrow of a dictatorship bya non-violent revolution.[26]

It is a founding member of the United Nations, World Trade Organization,Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, and the East Asia Summit. It also hosts the headquarters of the Asian Development Bank.[27] The Philippines is considered to be anemerging market and a newly industrialized country,[28] which has an economy transitioning from being one based on agriculture to one based more on services and manufacturing.[29] It is one of the only two predominantlyChristian nations in Southeast Asia, the other being East Timor.

Etymology

The Philippines was named in honor of King Philip II of Spain. Spanish explorer Ruy López de Villalobos, during his expedition in 1542, named the islands of Leyte and SamarFelipinas after the then-Prince of Asturias. Eventually the name Las Islas Filipinas would be used to cover all the islands of the archipelago. Before that became commonplace, other names such as Islas del Poniente (Islands of the West) and Magellan’s name for the islands San Lázaro were also used by the Spanish to refer to the islands.[30][31][32][33][34]

The official name of the Philippines has changed several times in the course of its history. During the Philippine Revolution, the Malolos Congress proclaimed the establishment of the República Filipina or the Philippine Republic. From the period of the Spanish–American War (1898) and the Philippine–American War (1899–1902) until the Commonwealth period (1935–46), American colonial authorities referred to the country as the Philippine Islands, a translation of the Spanish name.[25] From the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the namePhilippines began to appear and it has since become the country’s common name. Since the end of World War II, the official name of the country has been the Republic of the Philippines.[35]

History

Prehistory

The Tabon Caves are the site of one of the oldest human remains known in the Philippines, the Tabon Man

The metatarsal of the Callao Man, reliably dated by uranium-series datingto 67,000 years ago is the oldest human remnant found in the archipelago to date.[36] This distinction previously belonged to the Tabon Man of Palawan, carbon-dated to around 26,500 years ago.[37][38] Negritos were also among the archipelago’s earliest inhabitants, but their first settlement in the Philippines has not been reliably dated.[39]

There are several opposing theories regarding the origins of ancient Filipinos. F. Landa Jocano theorizes that the ancestors of the Filipinos evolved locally. Wilhelm Solheim‘s Island Origin Theory[40] postulates that the peopling of the archipelago transpired via trade networks originating in the Sundaland area around 48,000 to 5000 BC rather than by wide-scale migration. The Austronesian Expansion Theoryexplains that Malayo-Polynesians coming from Taiwan began migrating to the Philippines around 4000 BC, displacing earlier arrivals.[41]

The most widely accepted theory, based on linguistic and archeological evidence, is the “Out-of-Taiwan” model, which hypothesizes that Austronesians from Taiwan, who were themselves descended from the neolithic civilizations of the Yangtze river such as the Liangzhu culture,[42] began migrating to the Philippines around 4000 BC, displacing earlier arrivals.[41][43] During the neolithic period, a “jade culture” is said to have existed as evidenced by tens of thousands of exquisitely crafted jade artifacts found in the Philippines dated to 2000 BC.[44][45]

The jade is said to have originated nearby in Taiwan and is also found in many other areas in insular and mainland Southeast Asia. These artifacts are said to be evidence of long range communication between prehistoric Southeast Asian societies.[46] By 1000 BC, the inhabitants of the archipelago had developed into four kinds of social groups: hunter-gatherer tribes, warrior societies, highland plutocracies, and port principalities.[47]

Precolonial epoch

The current demarcation between the Prehistory and the Early history of the Philippines is 21 April 900, which is the equivalent on the Proleptic Gregorian calendar for the date indicated on the Laguna Copperplate Inscription—the earliest known surviving written record to come from the Philippines.[48] This date came in the middle of what anthropologists refer to as the Philippines’ “Emergent Phase” (1st–14th centuries CE), which was characterized by newly emerging socio-cultural patterns, the initial development of large coastal settlements, greater social stratification and specialization, and the beginnings of local and international trade.[49] By the 1300s, a number of the large coastal settlements had become progressive trading centers, and became the focal point of societal changes, ushering complex lifeways which characterized what F. Landa Jocano called the “Barangic Phase” of early Philippine history, beginning from the 14th century through the arrival of Spanish colonizers and the beginning of the Philippines’ colonial period.[49]

The discovery of iron at around the 1st century AD created significant social and economic changes which allowed settlements to grow larger and develop new social patterns, characterized by social stratification and specialization.[49]

Some of these polities, particularly the coastal settlements at or near the mouths of large rivers,[50] eventually developed substantial trade contacts with the early trading powers of Southeast Asia, most importantly the Indianized kingdoms of Malaysia and Java, the various dynasties of China,[50] Thailand,[51] and later, the Muslim Sultanate of Brunei.[52] They also traded with Vietnam,[51] Japan,[53] and other Austronesian islands.[54]

Based on archeological findings, trade with China is believed to have begun in the Tang dynasty, but grew more extensive during the Song dynasty.[52] By the 2nd millennium CE, some (but not all) Philippine polities were known to have sent trade delegations which participated in the Tributary system enforced by the Chinese imperial court.[52] These “tributary states” nominally acknowledged the Sinocentric system which saw China and the imperial court as the cultural center of the world. Among the early Philippine polities, this arrangement fulfilled the requirements for trade with China, but did not actually translate into political or military control.[52][50]

The Ifugao/Igorot people utilized terrace farming in the steep mountainous regions of northern Philippines over 2000 years ago.

Regarding the relations of early Philippine polities with the various state-level polities of Indonesia and Malaysia, legendary accounts often mention the interaction of early Philippine polities with the Srivijaya empire, but there is not much archeological evidence to definitively support such a relationship.[49] Considerable evidence exists, on the other hand, for extensive trade with the Majapahit empire.[55]

The exact scope and mechanisms of Indian cultural influences on early Philippine polities are still the subject of some debate among Southeast Asian historiographers,[49][56] but the current scholarly consensus is that there was probably little or no direct trade between India and the Philippines,[49][56] and Indian cultural traits, such as linguistic terms and religious practices,[55] filtered in during the 10th through the early 14th centuries, through early Philippine polities’ relations with the Hindu Majapahit empire.[49] The Philippine archipelago is thus one of the countries, (others include Afghanistan and Southern Vietnam) just at the outer edge of what is considered the “Greater Indian cultural zone”.[56]

The early polities of the Philippine archipelago were typically characterized by a three-tier social structure.[49][50] Although different cultures had different terms to describe them, this three-tier structure invariably consisted of an apex nobility class, a class of “freemen”, and a class of dependent debtor-bondsmen called “alipin” or “oripun.”[49][50] Among the members of the nobility class were leaders who held the political office of “Datu,” which was responsible for leading autonomous social groups called “barangay” or “dulohan”.[49] Whenever these barangays banded together, either to form a larger settlement[49] or a geographically looser alliance group,[50] the more senior or respected among them would be recognized as a “paramount datu”, variedly called a Lakan, Sultan, Rajah, or simply a more senior Datu.[52][49][57]

Early historic Coastal Polities

The Laguna Copperplate Inscription, c. 900. The oldest known historical record found in the Philippines, discovered at Lumban, Laguna.

The earliest historical record of these kingdoms is the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, which indirectly refers to the Tagalog settlement of Tondo(c. before 900–1589) and two to three other settlements believed to be located somewhere near Tondo, as well as a settlement near Mt. Diwata in Mindanao, and the temple complex of Medang in Java.[48] Although the precise political relationships between these polities is unclear in the text of the inscription, the artifact is usually accepted as evidence of intra- and inter-regional political linkages as early as 900 CE.[48][52][50] By the arrival of the earliest European ethnographers during the 1500s, Tondo was led by the paramount ruler called a “Lakan“.[52][50] It had grown into a major trading hub, sharing a monopoly with the Rajahnate of Maynila over the trade of Ming dynasty[58] products throughout the archipelago.[52]This trade was significant enough that the Yongle Emperor appointed a Chinese governor named Ko Ch’a-lao to oversee it.[59][60]

The next historical record referred a location in the Philippines is Volume 186 of official history of the Song dynasty which describes the “country” of Ma-i (c. before 971 – after 1339). Song dynasty traders visited Ma-i annually, and their accounts described Ma-i’s geography, trade products, and the trade behaviors of its rulers.[61] Because the descriptions of Mai’s location in these accounts are not clear, there is some dispute about Mai’s possible location, with some scholars believing it was located in Bay, Laguna,[62] and others believing it was on the island of Mindoro.[38]

The official history of the Song dynasty next refers to the Rajahnate of Butuan(c. before 1001–1756) in northeastern Mindanao which is the first polity from the Philippine archipelago recorded as having sent a tribute mission to the Chinese empire – on March 17, 1001 CE. Butuan attained prominence under the rule of Rajah Sri Bata Shaja,[54] who was from a Buddhist ruling-class governing a Hindu nation. This state became powerful due to the local goldsmith industry and it also had commercial ties and a diplomatic rivalry with the Champa civilization.

The Kedatuan of Madja-as (c. 1200–1569) was founded following a civil war in collapsing Srivijaya, wherein loyalists of the Malay datus of Srivijaya defied the invading Chola dynasty and its puppet-Rajah, called Makatunao, and set up a guerrilla-state in the islands of the Visayas. Its founding datu, Puti, had purchased land for his new realms from the aboriginal Ati hero, Marikudo.[63][verification needed] Madja-as was founded on Panay island (named after the destroyed state of Pannai allied under Srivijaya which was located in Sumatra). Afterwards, the people of Madja-as often raided the port cities of southern China and warred with the Chinese navy.[64]

The Rajahnate of Cebu[65] (c. 1200–1565) was a neighbor of Madja-as in the Visayas led by Rajamuda Sri Lumay, a monarch with partial Tamil descent. This state grew wealthy by making use of the inter-island shipping within the archipelago.[66] Both the Rajahnates of Butuan and Cebu were allied to each other and they also maintained contact and had trade routes with Kutai, a Hindu country[67] in south Borneo established by Indian traders.[68]

The earliest legendary date mentioning the Rajahnate of Maynila (c. 1258–1571) on the island of Luzon across the Pasig River from Tondo has to do with the naval victory of the Bruneian Rajah Ahmad over the Majapahit Rajah Avirjirkaya, who ruled a prior pre-Muslim settlement in the same location.[52] Chinese records of this period also mention a polity called “Luzon.” This is believed to be a reference to Maynila since Portuguese and Spanish accounts from the 1520s explicitly state that “Luçon” and “Maynila” were “one and the same”,[52] although some historians argue that since none of these observers actually visited Maynila, “Luçon” may simply have referred to all the Tagalog and Kapampangan polities that rose up on the shores of Manila Bay.[69] Either way, from the early 1500s to as late as the 1560s, this seafaring people was referred to in Portuguese Malacca as Luções, and they participated in trading ventures and military campaigns in Myanmar,Malacca and East Timor[70][71][72] where they were employed as traders and mercenaries.[73][74][75]

In northern Luzon, the Wangdom of Pangasinan (c. 1406–1576) sent emissaries to China in 1406–1411.[76]

The 1300s saw the arrival and eventual spread of Islam in the Philippine archipelago. In 1380, Karim ul’ Makdum and Shari’ful Hashem Syed Abu Bakr, anArab trader born in Johore, arrived in Sulu from Malacca and established theSultanate of Sulu by converting Sulu’s rajah, Rajah Baguinda Ali and marrying his daughter.[77][78] At the end of the 15th century, Shariff Mohammed Kabungsuwan ofJohor introduced Islam in the island of Mindanao and established the Sultanate of Maguindanao. The sultanate form of government extended further into Lanao.[79]

Islam then started to spread out of Mindanao in the south and went into Luzon in the north. Manila in Luzon was Islamized during the reign of Sultan Bolkiah in 1485 to 1521. This was accomplished because the Sultanate of Brunei subjugated Tondo by defeating Rajah Gambang in battle and thereafter installing the Muslim rajah, Rajah Salalila to the throne and by establishing the Bruneian puppet-state of the Rajahnate of Maynila.[80][81][82][83] Sultan Bolkiah also married Laila Mecana, the daughter of Sulu Sultan Amir Ul-Ombra to expand Brunei‘s influence in both Luzon and Mindanao.[84] The Muslims then proceeded to wage wars and conduct slave-raids against the Visayans.[85] Participating in the Muslim raids, the Sultanate of Ternate consequently destroyed theKedatuan of Dapitan in Bohol.[86] The Rajahnates of Butuan and Cebu also endured slave raids from, and waged wars against the Sultanate of Maguindanao.[87]

The rivalries between the Datus, Rajahs, Sultans, and Lakans eventually eased Spanish colonization. Furthermore, the islands were sparsely populated[88] due to consistent natural disasters[89] and inter-kingdom conflicts. Therefore, colonization was made easy and the small states of the archipelago quickly became incorporated into the Spanish Empire and were Hispanicized and Christianized.[90]

Colonial era

Spanish rule

In 1521, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan‘s expedition arrived in the Philippines, claimed the islands for Spain and was then killed at the Battle of Mactan.[91] Colonization began when Spanish explorer Miguel López de Legazpiarrived from Mexico in 1565 and formed the first Hispanic settlements in Cebu. After relocating to Panay island and consolidating a coalition of native Visayan allies, Hispanic soldiers and Latin-American recruits, the Spaniards then invaded Islamic Manila, therein they put down the Tondo Conspiracy and exiled the conspirators toGuam and Guerrero.[92] Under Spanish rule, they established Manila as the capital of the Spanish East Indies (1571).[93]

They also defeated the Chinese warlord Limahong.[94][95] To counteract the Islamization of the Philippines, the Spanish then conducted the Castilian War which was aimed against the Sultanate of Brunei[96][97] and war was also waged against the Sultanate of Ternate and Tidore (in response to Ternatean slaving and piracy against Spain’s allies: Bohol and Butuan).[98] The Spanish considered their war with the Muslims in Southeast Asia an extension of the Reconquista, a centuries-long campaign to retake and rechristianize the Spanish homeland which was invaded by the Muslims of the Umayyad Caliphate. The Spanish expeditions into the Philippines were also part of a larger Ibero-Islamic world conflict[99] that included a rivalry with the Ottoman Caliphate which had a center of operations at its nearby vassal, the Sultanate of Aceh.[100] Consequently, fortifications were also set up in Taiwanand the Maluku islands. These were abandoned and the Spanish soldiers, along with the newly Christianized Papuannatives of the Moluccas, withdrew back to the Philippines in order to re-concentrate their military forces because of a threatened invasion by the Japan-born Ming-dynasty loyalist, Koxinga, ruler of the Kingdom of Tungning.[101] However, the planned invasion was aborted. Meanwhile, settlers were sent to the Pacific islands of Palau and the Marianas.[102]

Spanish rule eventually contributed significantly to bringing political unity to the fragmented states of the archipelago. From 1565 to 1821, the Philippines was governed as a territory of the Mexico-based Viceroyalty of New Spain and then was administered directly from Madrid after the Mexican War of Independence. The Manila galleons, the largest wooden ships ever built, were constructed in Bicol and Cavite.[103] The Manila galleons were accompanied with a large naval escort as it traveled to and from Manila and Acapulco.[104] The galleons sailed once or twice a year, between the 16th and 19th centuries.[105] The Manila Galleons brought with them goods,[106] settlers[107] and military reinforcements destined for the Philippines, from Latin America.[108]

Trade introduced foodstuffs such as maize, tomatoes, potatoes, chili peppers,chocolate and pineapples from Mexico and Peru. Within the Philippines, theMarquisate of Buglas was established and the rule of it was awarded to Sebastian Elcano and his crew, the survivors of the first circumnavigation of the world, as well as his descendants. New towns were also created[95] and Catholic missionaries converted most of the lowland inhabitants to Christianity.[109] They also founded schools, a university, hospitals and churches which were built along the Earthquake Baroque architectural style.[110] To defend their settlements, the Spaniards constructed and manned a network of military fortresses (called “Presidios“) across the archipelago.[111] The Spanish also decreed the introduction of free public schooling in 1863.[112] As a result of these policies the Philippine population increased exponentially.[113][114]

During its rule, Spain quelled various indigenous revolts. There were also several external military challenges from Chinese and Japanese pirates, the Dutch, the English, the Portuguese and the Muslims of Southeast Asia. Those challengers were fought off despite the hostile forces having encircled the Philippine archipelago in a crescent formed from Japan to Indonesia. British forces occupied Manila from 1762 to 1764 in an extension of the fighting of the Seven Years’ War. Spanish rule was restored following the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[90][115][116] The Spanish–Moro conflict lasted for several hundred years. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Spain conquered portions of Mindanao and the Moro Muslims in theSulu Sultanate formally recognized Spanish sovereignty.

Photograph of armed Filipino revolutionaries known as Katipuneros.

In the 19th century, Philippine ports opened to world trade and shifts started occurring within Filipino society. Many Spaniards born in the Philippines (criollos)[117] and those of mixed ancestry (mestizos) became wealthy and an influx of Latin American immigrants[118] opened up government positions traditionally held by Spaniards born in the Iberian Peninsula (peninsulares). The ideals of revolution also began to spread through the islands. Criollo dissatisfaction resulted in the 1872Cavite Mutiny that was a precursor to the Philippine Revolution.[90][119][120][121]

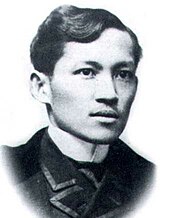

Revolutionary sentiments were stoked in 1872 after three priests—Mariano Gómez,José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora (collectively known as Gomburza)—were accused of sedition by colonial authorities and executed.[119][120] This would inspire a propaganda movement in Spain, organized by Marcelo H. del Pilar, José Rizal, and Mariano Ponce, lobbying for political reforms in the Philippines. Rizal was eventually executed on December 30, 1896, on charges of rebellion.[122] As attempts at reform met with resistance, Andrés Bonifacio in 1892 established the secret society called the Katipunan, who sought independence from Spain through armed revolt.[121]

Bonifacio and the Katipunan started the Philippine Revolution in 1896. A faction of the Katipunan, the Magdalo of Caviteprovince, eventually came to challenge Bonifacio’s position as the leader of the revolution and Emilio Aguinaldo took over. In 1898, the Spanish–American War began in Cuba and reached the Philippines. Aguinaldo declared Philippine independence from Spain in Kawit, Cavite on June 12, 1898, and the First Philippine Republic was established in theBarasoain Church in the following year.[90]

American rule

The islands were ceded by Spain to the United States as a result of the latter’s victory in the Spanish–American War.[123] A compensation of US$20 million was paid to Spain according to the terms of the 1898 Treaty of Paris.[124] As it became increasingly clear the United States would not recognize the nascent First Philippine Republic, the Philippine–American War broke out, the First Republic was defeated, and the archipelago was administered under an Insular Government.[125] The war resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of combatants as well as a couple of hundred thousand civilians, mostly from a cholera epidemic.[125][126][127][128]

The Americans then suppressed other rebellious sub-states: mainly, the waningSultanate of Sulu, as well as the insurgent Tagalog Republic, the Cantonal Republic of Negros in the Visayas, and the Republic of Zamboanga in Mindanao.[129][130]During this era, a renaissance in Philippine culture occurred, with the expansion of Philippine cinema andliterature.[131][132][133] Daniel Burnham built an architectural plan for Manila which would have transformed it into a modern city.[134] In 1935, the Philippines was granted Commonwealth status with Manuel Quezon as president. He designated a national language and introduced women’s suffrage and land reform.[135][136]

Japanese rule

Plans for independence over the next decade were interrupted by World War II when the Japanese Empire invaded and the Second Philippine Republic of José P. Laurel was established as a collaborator state. Many atrocities and war crimes were committed during the war such as the Bataan Death March and the Manila massacre that culminated with the Battle of Manila.[137] In 1944, Quezon died in exile in the United States and Sergio Osmeña succeeded him. The Allied Forcesthen employed a strategy of island hopping towards the Philippine archipelago, in the process, retaking territory conquered by Imperial Japan.

From mid-1942 through mid-1944, the Filipino guerrilla resistance[138][139] had been supplied and encouraged by U.S. Navy submarines and a few parachute drops, so that the guerrillas could harass the Japanese Army and take control of the rural areas, jungles and mountains – thus, the Japanese Empire only controlled 12 out of 48 provinces.[140] While remaining loyal to the United States, many Filipinos hoped and believed that liberation from the Japanese would bring them freedom and their already-promised independence.

Eventually, the largest naval battle in history, according to gross tonnage sunk, the Battle of Leyte Gulf, occurred when Allied forces started the liberation of the Philippines from the Japanese Empire.[141][142] Allied troops defeated the Japanesein 1945. By the end of the war it is estimated that over a million Filipinos had died.[143][144][145]

Postcolonial period

On October 11, 1945, the Philippines became one of the founding members of the United Nations.[146] The following year, on July 4, 1946, the Philippines was officially recognized by the United States as an independent nation through the Treaty of Manila, during the presidency of Manuel Roxas.[5] Disgruntled remnants of the communist Hukbalahap[147]continued to roam the countryside but were put down by President Elpidio Quirino‘s successor Ramon Magsaysay.[148][149] Magsaysay’s successor, Carlos P. Garcia, initiated the Filipino First Policy,[150] which was continued by Diosdado Macapagal, with celebration of Independence Day moved from July 4 to June 12, the date of Emilio Aguinaldo‘sdeclaration,[151][152] while furthering the claim on the eastern part of North Borneo.[153][154]

In 1965, Macapagal lost the presidential election to Ferdinand Marcos. Early in his presidency, Marcos initiated numerous infrastructure projects but was accused of massive corruption and embezzling billions of dollars in public funds.[155] Nearing the end of his term, Marcos declared Martial Law on September 21, 1972.[156] This period of his rule was characterized by political repression, censorship, and human rights violations but the US were steadfast in their support.[157]

On August 21, 1983, Marcos’ chief rival, opposition leader Benigno Aquino, Jr., was assassinated on the tarmac at Manila International Airport. Marcos eventually called snap presidential elections in 1986.[158] Marcos was proclaimed the winner, but the results were widely regarded as fraudulent, leading to the People Power Revolution. Marcos and his allies fled toHawaii and Aquino’s widow, Corazon Aquino was recognized as president.[158][159]

Contemporary history

The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo is the second largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century.

The return of democracy and government reforms beginning in 1986 were hampered by national debt, government corruption, coup attempts, disasters, a persistent communist insurgency,[160] and a military conflict with Moro separatists.[161] During Corazon Aquino‘s administration, U.S. forces withdrew from the Philippines, due to the rejection of the U.S. Bases Extension Treaty,[162][163] and leading to the official transfer of Clark Air Base in November 1991 and Subic Bay to the government in December 1992.[164][165] The administration also faced a series of natural disasters, including the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in June 1991.[166][167]After introducing a constitution that limited presidents to a single term, Aquino did not stand for re-election.

Aquino was succeeded by Fidel V. Ramos, who won the Philippine presidential election held in May 1992. During this period the country’s economic performance remained modest, with a 5–7 percent GDP growth rate.[168] However, the political stability and economic improvements, such as the peace agreement with theMoro National Liberation Front in 1996,[169] were overshadowed by the onset of the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[170][171] On his Presidency the death penalty was revived in the light of the Rape-slay case of Eileen Sarmienta and Allan Gomez in 1993 and the first person to be executed was Leo Echegaray in 1999.[172]

Ramos’ successor, Joseph Estrada assumed office in June 1998 and managed to regain the economy from −0.6% growth to 3.4% by 1999 amidst the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[173][174][175] The government had announced a war against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front in March 2000 and neutralized the camps including the headquarters of the insurgents.[176][177] In the middle of ongoing conflict with the Abu Sayyaf,[178] accusations of alleged corruption, and a stalled impeachment process, Estrada‘s administration was overthrown by the 2001 EDSA Revolution and succeeded by his Vice President,Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo on January 20, 2001.[179]

In Arroyo‘s 9-year administration, The economy experienced GDP growth from 4% in 2002 to 7% growth in 2007 with the completion of infrastructure projects like the LRT Line 2 in 2004[180] and managed to avoid the Great Recession.[181]Nevertheless, it was tied with graft and political scandals like the Hello Garci scandal pertaining to the alleged manipulation of votes in the 2004 presidential elections.[182][183][184][185] On November 23, 2009, the Maguindanao massacre led to the murder of 34 journalists.[186][187]

Benigno Aquino III won the 2010 national elections and served as the 15th President of the Philippines. He was the third youngest person to be elected president and the first to be a bachelor,[188] beginning with the 2010 Manila hostage crisisthat caused deeply strained relations between Manila and Hong Kong for a time. During the previous years, TheFramework Agreement on the Bangsamoro was signed on October 15, 2012, as the first step of the creation of an autonomous political entity named Bangsamoro.[189] However, territorial disputes in eastern Sabah and the South China Sea have escalated.[190][191][192]

The economy performed well at 7.2% GDP growth, the second fastest in Asia.[193] Aquino signed the Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013, commonly known as K–12 program in May 15, 2013 aiming to enhance the educational system in the country.[194] On November 8, 2013, Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) struck and heavily devastated the country, especially in the Visayas.[195][196] On April 28, 2014, when United States President Barack Obama visited the Philippines, the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, was signed.[197][198][199] From January 15 to 19, 2015, Pope Francis stayed in the Philippines for an apostolic and state visit and paid visits to the victims of Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda).[200][201] On January 25, 2015, 44 members of the Philippine National Police–Special Action Force were killed after a clash took place inMamasapano, Maguindanao putting efforts to pass the Bangsamoro Basic Law into law in an impasse.[202][203] On December 20, 2015, Pia Wurtzbach won the Miss Universe 2015, making her the third Filipino to win the Miss Universe title following Gloria Diaz in 1969 and Margarita Moran in 1973.[204] On January 12, 2016, the Philippine Supreme Court upheld the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement paving the way for the return of United States Armed Forces bases into the country.[205] On March 23, 2016, Diwata-1 was launched to the International Space Station (ISS), becoming the country’s first micro-satellite and the first satellite to be built and designed by Filipinos.[206]

Rodrigo Duterte takes his oath as he is sworn in as the 16th President of the Philippines

Former Davao City mayor Rodrigo Duterte of PDP–Laban won the 2016 presidential election becoming the first president from Mindanao.[207] On July 12, 2016, thePermanent Court of Arbitration ruled in favor of the Philippines in its case against China’s claims in the South China Sea.[208] On August 1, 2016, the Duterte administration launched a 24-hour complaint office accessible to the public through a nationwide hotline, 8888, and changed the nationwide emergency telephone number from 117 to 911.[209][210] After winning the Presidency, Duterte launched an intensified anti-drug campaign to fulfill a campaign promise of wiping out criminality in six months.[211] By March 2017, the death toll for the Philippine Drug War passed 8,000 people, with 2,679 killed in legitimate police operations and the rest the government claims to be homicide cases.[212][213][214]

Politics

The Philippines has a democratic government in the form of a constitutional republic with a presidential system.[215] It is governed as a unitary state with the exception of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), which is largely free from the national government. There have been attempts to change the government to afederal, unicameral, or parliamentary government since the Ramos administration.[216][217]

The President functions as both head of state and head of government and is thecommander-in-chief of the armed forces. The president is elected by popular vote for a single six-year term, during which he or she appoints and presides over thecabinet.[218] The bicameral Congress is composed of the Senate, serving as theupper house, with members elected to a six-year term, and the House of Representatives, serving as the lower house, with members elected to a three-year term.[218]

Senators are elected at large while the representatives are elected from both legislative districts and through sectoral representation.[218] The judicial power is vested in the Supreme Court, composed of a Chief Justice as its presiding officer and fourteen associate justices, all of whom are appointed by the President from nominations submitted by the Judicial and Bar Council.[218]

Foreign relations

The Philippines’ international relations are based on trade with other nations and the well-being of the 10 million overseas Filipinos living outside the country.[219] As a founding and active member of the United Nations, the Philippines has been elected several times into the Security Council. Carlos P. Romulo was a former President of the United Nations General Assembly. The country is an active participant in theHuman Rights Council as well as in peacekeeping missions, particularly in East Timor.[220][221][222]

In addition to membership in the United Nations, the Philippines is also a founding and active member of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), an organization designed to strengthen relations and promote economic and cultural growth among states in the Southeast Asian region.[223] It has hosted severalsummits and is an active contributor to the direction and policies of the bloc.[224]

The Philippines values its relations with the United States.[219] It supported the United States during the Cold War and the War on Terror and is a major non-NATO ally. Despite this history of goodwill, controversies related to the presence of the now former U.S. military bases in Subic Bay and Clark and the current Visiting Forces Agreement have flared up from time to time.[219] Japan, the biggest contributor of official development assistance to the country,[225] is thought of as a friend. Although historical tensions still exist on issues such as the plight of comfort women, much of the animosity inspired by memories of World War II has faded.[226]

Relations with other nations are generally positive. Shared democratic values ease relations with Western and European countries while similar economic concerns help in relations with other developing countries. Historical ties and cultural similarities also serve as a bridge in relations with Spain.[227][228][229] Despite issues such as domestic abuse and war affecting overseas Filipino workers,[230][231] relations with Middle Eastern countries are friendly as seen in the continuous employment of more than two million overseas Filipinos living there.[232]

With communism no longer the threat it once was, once hostile relations in the 1950s between the Philippines and Chinahave improved greatly. Issues involving Taiwan, the Spratly Islands, and concerns of expanding Chinese influence, however, still encourage a degree of caution.[226] Recent foreign policy has been mostly about economic relations with its Southeast Asian and Asia-Pacific neighbors.[219]

The Philippines is an active member of the East Asia Summit (EAS), the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), theLatin Union, the Group of 24, and the Non-Aligned Movement.[218] It is also seeking to strengthen relations with Islamic countries by campaigning for observer status in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.[233][234]

On October 24, 2017, Russia’s Minister of Defence Sergey Shoygu and Philippines Secretary of Defense Delfin Lorenzanasigned the Russia-Philippines Agreement for Military-Technical Cooperation at the ASEAN Convention Center in Clark, Pampanga.[235] On October 25, 2017, Russia donated 5,000 AK-74M Kalashnikov assault rifles, 1 million units of ammunition and 5,000 units of steel helmets.[236] Russia’s Pacific Fleet also gave the Armed Forces of the Philippines 20 military trucks. Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte personally oversaw the transition on the Russian destroyer Admiral Panteleyev which was docked in Manila.[237]

Military

The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) are responsible for national security and consist of three branches: the Philippine Air Force, the Philippine Army, and the Philippine Navy (includes theMarine Corps).[238][239][240] The Armed Forces of the Philippines are avolunteer force.[241] Civilian security is handled by the Philippine National Police under the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG).[242][243]

In the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, the largest separatist organization, the Moro National Liberation Front, is now engaging the government politically. Other more militant groups like the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, the communist New People’s Army, and theAbu Sayyaf have previously kidnapped foreigners for ransom, particularly on the southern island of Mindanao.[245][246][247][248] Their presence has decreased in recent years due to successful security provided by the Philippine government.[249][250] At 1.1 percent of GDP, the Philippines spent less on its military forces than the regional average. As of 2014 Malaysia and Thailand were estimated to spend 1.5%, China 2.1%, Vietnam 2.2% and South Korea 2.6%.[251][252]

The Philippines has been an ally of the United States since World War II. A mutual defense treaty between the two countries was signed in 1951. The Philippines supported American policies during the Cold War and participated in theKorean and Vietnam wars. It was a member of the now dissolved SEATO, a group that was intended to serve a role similar to NATO and that included Australia, France, New Zealand, Pakistan, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[253] After the start of the War on Terror, the Philippines was part of the coalition that gave support to the United States in Iraq.[254]

Administrative divisions

The Philippines is divided into three island groups: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. These are further divided into 17regions, 81 provinces, 145 cities, 1,489 municipalities, and 42,036 barangays.[255] In addition, Section 2 of Republic Act No. 5446 asserts that the definition of the territorial sea around the Philippine archipelago does not affect the claim over the eastern part of Sabah.[256][257]

| [show]

Administrative Divisions of the Philippines

|

Administrative regions

Regions in the Philippines are administrative divisions that serve primarily to organize the provinces of the country for administrative convenience. The Philippines is divided into 17 regions (16 administrative and 1 autonomous). Most government offices are established by region instead of individual provincial offices, usually (but not always) in the city designated as the regional center. As of 2015, CALABARZON was the most populated region while the National Capitol Region (NCR) the most densely populated.

10 Most Populous Regions of the Philippines (2015)[258]

| Rank |

Designation |

Name |

Area |

Population (as of 2015) |

% of Population |

Population density |

| 1st |

Region IV |

CALABARZON |

16,873.31 km2(6,514.82 sq mi) |

14,414,774 |

14.27% |

850/km2(2,200/sq mi) |

| 2nd |

NCR |

National Capital Region |

619.57 km2(239.22 sq mi) |

12,877,253 |

12.75% |

21,000/km2(54,000/sq mi) |

| 3rd |

Region III |

Central Luzon |

22,014.63 km2(8,499.90 sq mi) |

11,218,177 |

11.11% |

510/km2(1,300/sq mi) |

| 4th |

Region VII |

Central Visayas |

10,102.16 km2(3,900.47 sq mi) |

6,041,903 |

5.98% |

600/km2(1,600/sq mi) |

| 5th |

Region V |

Bicol Region |

18,155.82 km2(7,010.00 sq mi) |

5,796,989 |

5.74% |

320/km2(830/sq mi) |

| 6th |

Region I |

Ilocos Region |

16,873.31 km2(6,514.82 sq mi) |

5,026,128 |

4.98% |

300/km2(780/sq mi) |

| 7th |

Region XI |

Davao Region |

20,357.42 km2(7,860.04 sq mi) |

4,893,318 |

4.85% |

240/km2(620/sq mi) |

| 8th |

Region X |

Northern Mindanao |

20,496.02 km2(7,913.56 sq mi) |

4,689,302 |

4.64% |

230/km2(600/sq mi) |

| 9th |

Region XII |

SOCCSKSARGEN |

22,513.30 km2(8,692.43 sq mi) |

4,545,276 |

4.50% |

200/km2(520/sq mi) |

| 10th |

Region VI |

Western Visayas |

12,828.97 km2(4,953.29 sq mi) |

4,477,247 |

4.43% |

350/km2(910/sq mi) |

Geography

Topography of the Philippines

The Philippines is an archipelago composed of about 7,641 islands[259] with a total land area, including inland bodies of water, of 300,000 square kilometers (115,831 sq mi).[260] Its 36,289 kilometers (22,549 mi) of coastline makes it the country with the 5th longest coastline in the world.[218][261] It is located between 116° 40′, and 126° 34′ E longitude and 4° 40′ and 21° 10′ N latitude and is bordered by the Philippine Sea[262] to the east, the South China Sea[263] to the west, and the Celebes Sea[264] to the south. The island of Borneo[265] is located a few hundred kilometers southwest and Taiwan is located directly to the north. The Moluccas and Sulawesi are located to the south-southwest and Palau is located to the east of the islands.[218]

Most of the mountainous islands are covered in tropical rainforest and volcanic in origin. The highest mountain is Mount Apo. It measures up to 2,954 meters (9,692 ft) above sea level and is located on the island of Mindanao.[266][267] The Galathea Depth in the Philippine Trench is the deepest point in the country and the third deepest in the world. The trench is located in the Philippine Sea.[268]

The longest river is the Cagayan River in northern Luzon.[269] Manila Bay, upon the shore of which the capital city of Manila lies, is connected to Laguna de Bay, the largest lake in the Philippines, by the Pasig River. Subic Bay, the Davao Gulf, and the Moro Gulf are other important bays. The San Juanico Strait separates the islands of Samar and Leyte but it is traversed by the San Juanico Bridge.[270]

Situated on the western fringes of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Philippines experiences frequent seismic and volcanic activity. The Benham Plateau to the east in the Philippine Sea is an undersea region active in tectonic subduction.[271]Around 20 earthquakes are registered daily, though most are too weak to be felt. The last major earthquake was the 1990 Luzon earthquake.[272]

Mayon is the Philippines’ most active volcano.

There are many active volcanoes such as the Mayon Volcano, Mount Pinatubo, andTaal Volcano. The eruption of Mount Pinatubo in June 1991 produced the second largest terrestrial eruption of the 20th century.[273] Not all notable geographic features are so violent or destructive. A more serene legacy of the geological disturbances is the Puerto Princesa Subterranean River, the area represents a habitat for biodiversity conservation, the site also contains a full mountain-to-the-sea ecosystem and has some of the most important forests in Asia.[274]

Due to the volcanic nature of the islands, mineral deposits are abundant. The country is estimated to have the second-largest gold deposits after South Africa and one of the largest copper deposits in the world.[275] It is also rich in nickel, chromite, and zinc. Despite this, poor management, high population density, and environmental consciousness have resulted in these mineral resources remaining largely untapped.[275] Geothermal energy is a product of volcanic activity that the Philippines has harnessed more successfully. The Philippines is the world’s second-biggest geothermal producer behind the United States, with 18% of the country’s electricity needs being met by geothermal power.[276]

Biodiversity

The Philippines’ rainforests and its extensive coastlines make it home to a diverse range of birds, plants, animals, and sea creatures.[277] It is one of the ten most biologically megadiverse countries.[278][279][280] Around 1,100 land vertebrate species can be found in the Philippines including over 100 mammal species and 170 bird species not thought to exist elsewhere.[281] The Philippines has among the highest rates of discovery in the world with sixteen new species of mammalsdiscovered in the last ten years. Because of this, the rate of endemism for the Philippines has risen and likely will continue to rise.[282] Native mammals include thepalm civet cat, the dugong, the cloud rat and the Philippine tarsier associated withBohol.

Although the Philippines lacks large mammalian predators, it does have some very large reptiles such as pythons andcobras, together with gigantic saltwater crocodiles. The largest crocodile in captivity, known locally as Lolong, was captured in the southern island of Mindanao.[283][284] The national bird, known as the Philippine eagle has the longest body of anyeagle, it generally measures 86 to 102 cm (2.82 to 3.35 ft) in length and weighs 4.7 to 8.0 kg (10.4 to 17.6 lb).[285][286] The Philippine eagle is part of the Accipitridae family and is endemic to the rainforests of Luzon, Samar, Leyte and Mindanao.

Philippine maritime waters encompass as much as 2,200,000 square kilometers (849,425 sq mi) producing unique and diverse marine life, an important part of theCoral Triangle.[256] The total number of corals and marine fish species was estimated at 500 and 2,400 respectively.[277][281] New records[287][288] and species discoveries[289][290][291] continuously increase these numbers underlining the uniqueness of the marine resources in the Philippines. The Tubbataha Reef in the Sulu Sea was declared a World Heritage Site in 1993. Philippine waters also sustain the cultivation of pearls, crabs, and seaweeds.[277][292]

With an estimated 13,500 plant species in the country, 3,200 of which are unique to the islands,[281] Philippine rainforests boast an array of flora, including many rare types oforchids and rafflesia.[293][294] Deforestation, often the result of illegal logging, is an acute problem in the Philippines. Forest cover declined from 70% of the Philippines’s total land area in 1900 to about 18.3% in 1999.[295] Many species are endangered and scientists say that Southeast Asia, which the Philippines is part of, faces a catastrophic extinction rate of 20% by the end of the 21st century.[296] According to Conservation International, “the country is one of the few nations that is, in its entirety, both a hotspot and a megadiversity country, placing it among the top priority hotspots for global conservation.”[293]

Climate

The Philippines has a tropical maritime climate that is usually hot and humid. There are three seasons: tag-init or tag-araw, the hot dry season or summer from March to May; tag-ulan, the rainy season from June to November; and tag-lamig, the cool dry season from December to February. The southwest monsoon (from May to October) is known as the Habagat, and the dry winds of the northeast monsoon (from November to April), the Amihan.[297] Temperatures usually range from 21 °C (70 °F) to 32 °C (90 °F) although it can get cooler or hotter depending on the season. The coolest month is January; the warmest is May.[218][298]

The average yearly temperature is around 26.6 °C (79.9 °F).[297] In considering temperature, location in terms of latitude and longitude is not a significant factor. Whether in the extreme north, south, east, or west of the country, temperatures at sea level tend to be in the same range. Altitude usually has more of an impact. The average annual temperature of Baguioat an elevation of 1,500 meters (4,900 ft) above sea level is 18.3 °C (64.9 °F), making it a popular destination during hot summers.[297]

Sitting astride the typhoon belt, most of the islands experience annual torrential rains and thunderstorms from July to October,[299] with around nineteen typhoons entering the Philippine area of responsibility in a typical year and eight or nine making landfall.[300][301][302] Annual rainfall measures as much as 5,000 millimeters (200 in) in the mountainous east coast section but less than 1,000 millimeters (39 in) in some of the sheltered valleys.[299] The wettest known tropical cyclone to impact the archipelago was the July 1911 cyclone, which dropped over 1,168 millimeters (46.0 in) of rainfall within a 24-hour period in Baguio.[303] Bagyo is the local term for a tropical cyclone in the Philippines.[303]

Economy

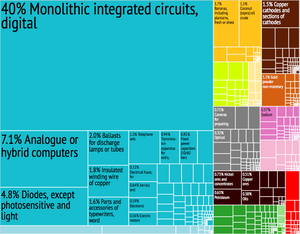

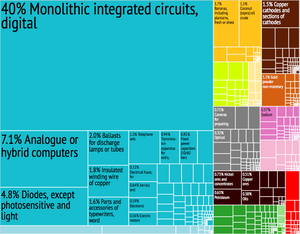

A proportional representation of the Philippines’ exports, 2012.

The Philippine economy is the 34th largest in the world, with an estimated 2017 gross domestic product (nominal) of $348.593 billion.[7]Primary exports include semiconductors and electronic products, transport equipment, garments, copper products, petroleum products,coconut oil, and fruits.[5] Major trading partners include the United States, Japan, China, Singapore, South Korea, the Netherlands, Hong Kong, Germany, Taiwan, and Thailand.[5] Its unit of currency is thePhilippine peso (₱ or PHP).[304]

A newly industrialized country, the Philippine economy has been transitioning from one based upon agriculture to an economy with more emphasis upon services and manufacturing. Of the country’s total labor force of around 40.813 Million,[5] the agricultural sector employs 30% of the labor force, and accounts for 14% of GDP. The industrial sector employs around 14% of the workforce and accounts for 30% of GDP. Meanwhile, the 47% of workers involved in the services sector are responsible for 56% of GDP.[306][307]

The unemployment rate as of 14 December 2014, stands at 6.0%.[308][309]Meanwhile, due to lower charges in basic necessities, the inflation rate eases to 3.7% in November.[310] Gross international reserves as of October 2013 are $83.201 billion.[311] The Debt-to-GDP ratio continues to decline to 38.1% as of March 2014[312][313] from a record high of 78% in 2004.[314] The country is a net importer[307] but it is also a creditor nation.[315]

After World War II, the Philippines was for a time regarded as the second wealthiest in East Asia, next only to Japan.[219][316][317] In the 1960s its economic performance started being overtaken. The economy stagnated under the dictatorship of President Ferdinand Marcos as the regime spawned economic mismanagement and political volatility.[219][317] The country suffered from slow economic growth and bouts of economic recession. Only in the 1990s with a program of economic liberalization did the economy begin to recover.[219][317]

The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis affected the economy, resulting in a lingering decline of the value of the peso and falls in the stock market. The extent it was affected initially was not as severe as that of some of its Asian neighbors. This was largely due to the fiscal conservatism of the government, partly as a result of decades of monitoring and fiscal supervision from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in comparison to the massive spending of its neighbors on the rapid acceleration of economic growth.[169] There have been signs of progress since. In 2004, the economy experienced 6.4% GDP growth and 7.1% in 2007, its fastest pace of growth in three decades.[318][319] Average annual GDP growth per capita for the period 1966–2007 still stands at 1.45% in comparison to an average of 5.96% for the East Asia and the Pacific region as a whole. The daily income for 45% of the population of the Philippines remains less than $2.[320][321][322]

The economy is heavily reliant upon remittances from overseas Filipinos, which surpass foreign direct investment as a source of foreign currency. Remittances peaked in 2010 at 10.4% of the national GDP, and were 8.6% in 2012 and in 2014, Philippines total worth of foreign exchange remittances was US$28 billion.[323][324] Regional development is uneven, with Luzon – Metro Manila in particular – gaining most of the new economic growth at the expense of the other regions,[325][326]although the government has taken steps to distribute economic growth by promoting investment in other areas of the country. Despite constraints, service industries such as tourism and business process outsourcing have been identified as areas with some of the best opportunities for growth for the country.[307][327]

Goldman Sachs includes the country in its list of the “Next Eleven” economies[328][329] but China and India have emerged as major economic competitors.[330] Goldman Sachs estimates that by the year 2050, it will be the 20th largest economy in the world.[331] HSBC also projects the Philippine economy to become the 16th largest economy in the world, 5th largest economy in Asia and the largest economy in the South East Asian region by 2050.[332][333][334] The Philippines is a member of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Asian Development Bankwhich is headquartered in Mandaluyong, the Colombo Plan, the G-77 and the G-24 among other groups and institutions.[5]

Transportation

The transportation infrastructure in the Philippines is relatively underdeveloped. This is partly due to the mountainous terrain and the scattered geography of the islands, but also the result of consistently low investment in infrastructure by successive governments. In 2013, about 3% of national GDP went towards infrastructure development – much lower than many of its neighbors.[335][336] There are 216,387 kilometers (134,457 mi) of roads in the Philippines, with only 61,093 kilometers (37,961 mi) of roads paved.[337]

Buses, jeepneys, taxis, and motorized tricycles are commonly available in major cities and towns. In 2007, there were about 5.53 million registered motor vehicles with registrations increasing at an average annual rate of 4.55%.[338]

The Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines manages airports and implementation of policies regarding safe air travel[339][340] with 85 public airports operational as of 2014.[341] Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA) serves theGreater Manila Area together with Clark International Airport. Philippine Airlines, Asia’s oldest commercial airline still operating under its original name, and Cebu Pacific, the leading low-cost airline, are the major airlines serving most domestic and international destinations.[342][343][344]

Expressways and highways are mostly located on the island of Luzon including the Pan-Philippine Highway, connecting the islands of Luzon, Samar, Leyte, and Mindanao,[345][346] the North Luzon Expressway, South Luzon Expressway, and theSubic–Clark–Tarlac Expressway.[347][348][349][350][351][352]

Rail transport in the Philippines only plays a role in transporting passengers within Metro Manila. The region is served by three rapid transit lines: LRT-1, and LRT-2and MRT-3.[353][354][355] In the past, railways served major parts of Luzon, and railroad services were available on the islands of Cebu and Negros. Railways were also used for agricultural purposes, especially in tobacco and sugar cane production. Rail freight transportation was almost non-existent as of 2014. A few transportation systems are under development: DOST-MIRDC and UP are implementing pre-feasibility studies on Automated Guideway Transit.[356][357][358] A so-called Hybrid Electric Road Train which is a long bi-articulated bus, was also being tested as of 2015.[359][360][361]

As an archipelago, inter-island travel using watercraft is often necessary.[362] The busiest seaports are Manila, Batangas, Subic, Cebu, Iloilo, Davao, Cagayan de Oro, and Zamboanga.[363] 2GO Travel andSulpicio Lines serve Manila, with links to various cities and towns through passenger vessels. The 919-kilometer (571 mi)Strong Republic Nautical Highway (SRNH), an integrated set of highway segments and ferry routes covering 17 cities was established in 2003.[364] The Pasig River Ferry Service serves the major rivers in Metro Manila, including the Pasig Riverand Marikina River having numerous stops in Manila, Makati, Mandaluyong, Pasig and Marikina.[365][366]

Science and technology

The Philippines has pursued efforts to improve the field of science and technology. TheDepartment of Science and Technology is the governing agency responsible for the development of coordination of science- and technology-related projects in the Philippines.[367]The National Scientist of the Philippines award is given to individuals that have contributed to different field of science in the country. Notable Filipino scientists include Maria Orosa, a food technologist famous for her formulated food products like calamansi nip, soyalac and thebanana ketchup,[368]

Fe del Mundo, a pediatrician whose pioneering work in pediatrics as an active medical practice spanned 8 decades,[369] Paulo Campos, a physician who was dubbed as “The Father of Nuclear Medicine in the Philippines” for his contributions in the field of nuclear medicine,[370]Ramon Barba, an inventor and horticulturist known for his method to induce more flowers in mango trees.[371]

Research organizations include the International Rice Research Institute, an international independent research and training organization established in 1960 with headquarters in Los Baños, Laguna,[372][373] focusing on the development of new rice varieties and rice crop management techniques to help farmers in the country improve their lives.[374] The Philippines bought its first satellite in 1996.[375] In 2016, the Philippines first micro-satellite, Diwata-1 was launched aboard the US Cygnus spacecraft.[376]

Communications

The Philippines has a sophisticated cellular phone industry and a high concentration of users. Text messaging is a popular form of communication and, in 2007, the nation sent an average of one billion SMS messages per day. Over five million mobile phone users also use their phones as virtual wallets, making it a leader among developing nations in providing financial transactions over cellular networks.[377][378][379] The Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company commonly known as PLDT is the leading telecommunications provider. It is also the largest company in the country.[377][380]

The National Telecommunications Commission is the agency responsible for the supervision, adjudication and control over all telecommunications services throughout the country.[381] There are approximately 383 AM and 659 FM radio stations and 297 television and 873 cable television stations.[382] On March 29, 1994, the country went live on the Internet via a 64 kbit/s connection from a router serviced by PLDT to a Sprint router in California.[383] Estimates for Internet penetration in the Philippines vary widely ranging from a low of 2.5 million to a high of 24 million people.[384][385] Social networking and watching videos are among the most frequent Internet activities.[386]

Tourism

Limestone cliffs of El Nido, Palawan.

The travel and tourism sector is a major contributor to the economy, contributing 7.1% to the Philippine GDP in 2013 [387] and providing 1,226,500 jobs or 3.2 percent of total employment.[388] 2,433,428 international visitors arrived from January to June 2014 up by 2.22% in the same period in 2013. South Korea, China, and Japan accounted for 58.78% while the Americas accounted for 19.28% and Europe 10.64%.[389] The Department of Tourism has responsibility for the management and promotion of the tourism sector.

The country’s rich biodiversity is one of the main tourist attractions with its beaches, mountains, rainforests, islands and diving spots among the most popular tourist destinations. As an archipelago consisting of about 7,500 islands, the Philippines has numerous beaches, caves and other rock formations. Boracay has glaring white sand beaches and was named as the best island in the world by Travel + Leisure in 2012.[390] The Banaue Rice Terraces in Ifugao, the historic town of Vigan in Ilocos Sur, the Chocolate Hills in Bohol, Magellan’s Cross in Cebu and the Tubbataha Reef in Visayas are other highlights.

The Philippines is also one of the favorite retirement destinations for foreigners due to its warm climate all year round, beaches and low cost of living.[391]

Water supply and sanitation

Among the achievements of the government in the Philippines are a high access to an improved water source of 92% in 2010; the creation of financially sustainable water service providers (“Water Districts”) in small and medium towns with the continuous long-term support of a national agency (the “Local Water Utilities Administration” LWUA); and the improvement of access, service quality and efficiency in Manila through two high-profle water concessions awarded in 1997.[392]

The challenges include limited access to sanitation services, high pollution of water resources, often poor drinking water quality and poor service quality, a fragmentation of executive functions at the national level among numerous agencies, and a fragmentation of service provision at the local level into many small service providers.[392]

In 2015 it was reported by the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation by WHO and UNICEF that 74% of the population had access to improved sanitation and that “good progress” had been made.[393] The access to improved sanitation was reported to be similar for the urban and rural population.[393]

Demographics

Population density per province as of 2009 per square kilometer.

The population of the Philippines increased from 1990 to 2008 by approximately 28 million, a 45% growth in that time frame.[394] The firstofficial census in the Philippines was carried out in 1877 and recorded a population of 5,567,685.[395]

It is estimated that half of the population resides on the island of Luzon. The 3.21% population growth rate between 1995 and 2000 decreased to an estimated 1.95% for the 2005–2010 period, but remains acontentious issue.[396][397] The population’s median age is 22.7 years with 60.9% aged from 15 to 64 years old.[5] Life expectancy at birth is 71.94 years, 75.03 years for females and 68.99 years for males.[398]Poverty Incidence significantly dropped to 21.6% in 2015 from 25.2% in 2012.[399]

Since the liberalization of United States immigration laws in 1965, the number of people in the United States having Filipino ancestry has grown substantially. In 2007 there were an estimated[400][401] 12 millionFilipinos living overseas.[402]

According to the official count the population of the Philippines hit 100 million at the time of midnight on July 27, 2014, making it the 12th country to reach this number.[403]

Cities

Metro Manila is the most populous of the 3 defined metropolitan areas in the Philippines and the 11th most populous in the world. as of 2007, census data showed it had a population of 11,553,427, comprising 13% of the national population.[404] Including suburbs in the adjacent provinces (Bulacan, Cavite, Laguna, andRizal) of Greater Manila, the population is around 21 million.[404][405]

Metro Manila’s gross regional product was estimated as of 2009 to be ₱468.4 billion (at constant 1985 prices) and accounts for 33% of the nation’s GDP.[406] In 2011 Manila ranked as the 28th wealthiest urban agglomeration in the world and the 2nd in Southeast Asia.[407]

Ethnic groups

Dominant ethnic groups by province.

According to the 2000 census, 28.1% of Filipinos are Tagalog, 13.1% Cebuano, 9% Ilocano, 7.6% Visayans/Bisaya (excluding Cebuano, Hiligaynon and Waray), 7.5% Hiligaynon, 6% Bikol, 3.4% Waray, and 25.3% as “others”,[5][408] which can be broken down further to yield more distinct non-tribal groups like the Moro, theKapampangan, the Pangasinense, the Ibanag, and theIvatan.[409] There are also indigenous peoples like theIgorot, the Lumad, the Mangyan, the Bajau, and the tribes of Palawan.[410]

Filipinos generally belong to several Asian ethnic groups classified linguistically as part of the Austronesian orMalayo-Polynesian speaking people.[410] It is believed that thousands of years ago Austronesian-speaking Taiwanese aborigines migrated to the Philippines from Taiwan, bringing with them knowledge of agriculture and ocean-sailing, eventually displacing the earlier Negrito groups of the islands.[411] Negritos, such as the Aeta and the Ati, are considered among the earliest inhabitants of the islands.[412]

Being at the crossroads of the West and East, the Philippines is also home to migrants from places as diverse as China, Spain, Mexico, United States, India, South Korea, and Japan. Two important non-indigenous minorities are theChinese and the Spaniards.

The Chinese, mostly descendants of immigrants fromFujian, China after 1898, number 2 million, although there are an estimated 27 percent of Filipinos who have partial Chinese ancestry,[413][414][415] stemming from precolonial and colonial Chinese migrants.[416] Intermarriage between the groups is evident in the major cities and urban areas.[417]

At least one-third of the population of Luzon, as well as old settlements in the Visayas and Zamboanga City at Mindanao (around 13.33% of the Philippine population), have partial Hispanic ancestry (from varying points of origin and ranging fromLatin America[418] to Spain).[419] Recent genetic studies confirm this partial European[420][421] and Latin-American ancestry.[422]

Other important non-indigenous minorities include Indians, Britons, and Japanese people. The descendants of mixed-race couples are known as mestizos.[423][424]

Languages

Population by mother tongue (2010)

| Tagalog |

24.44 % |

|

22,512,089 |

| Cebuano |

21.35 % |

|

19,665,453 |

| Ilokano |

8.77 % |

|

8,074,536 |

| Hiligaynon |

8.44 % |

|

7,773,655 |

| Waray |

3.97 % |

|

3,660,645 |

| Other local languages/dialects |

26.09 % |

|

24,027,005 |

| Other foreign languages/dialects |

0.09 % |

|

78,862 |

| Not reported/not stated |

0.01 % |

|

6,450 |

| TOTAL |

92,097,978 |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority |

Ethnologue lists 186 individual languages in the Philippines, 182 of which are living languages, while 4 no longer have any known speakers. Most native languages are part of thePhilippine branch of the Malayo-Polynesian languages, which is itself a branch of the Austronesian language family.[410] The only language not classified as an Austronesian language isChavacano which is a creole language of Mexican-Spanishand is classified as a Romance language.[425]

Filipino and English are the official languages of the country.[12] Filipino is a standardized version of Tagalog, spoken mainly in Metro Manila and other urban regions. Both Filipino and English are used in government, education, print, broadcast media, and business. In most towns, the local indigenous language is spoken. The Philippine constitution provides for the promotion of Spanish and Arabic on a voluntary and optional basis, although neither are used on as wide a scale as in the past.[12] Spanish, which was widely used as a lingua franca in the late nineteenth century, has since declined greatly in use, but is experiencing revival due to government promotions, while Arabic is mainly used in Islamic schools in Mindanao.[426] However, Spanish loanwords are still present today in many of the indigenous Philippine languages.[427]

Nineteen regional languages act as auxiliary official languages used as mediums of instruction: Aklanon, Bikol, Cebuano,Chavacano, Hiligaynon, Ibanag, Ilocano, Ivatan, Kapampangan, Kinaray-a, Maguindanao, Maranao, Pangasinan, Sambal,Surigaonon, Tagalog, Tausug, Waray, and Yakan.[2] Other indigenous languages such as, Cuyonon, Ifugao, Itbayat,Kalinga, Kamayo, Kankanaey, Masbateño, Romblomanon, Malay, and several Visayan languages are prevalent in their respective provinces.[428]

Languages not indigenous to the islands are also taught in select schools. Mandarin is used in Chinese schools catering to the Chinese Filipino community. Islamic schools in Mindanao teach Modern Standard Arabic in their curriculum.[429] French,German, Japanese, Korean, and Spanish are taught with the help of foreign linguistic institutions.[430] The Department of Education began teaching the Malay languages of Indonesian and Malaysian in 2013.[431]

Religion

The Philippines is an officially secular state, although Christianity is the dominant faith.[432] Census data from 2010 found that about 80.58% of the population professed Catholicism.[4] Around 37% regularly attend Mass and 29% identify as very religious.[433][434] Protestants are 10.8%[435][436] of the total population, mostly endorsing Evangelical Protestant denominations that were introduced by American missionaries at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, they are heavily concentrated in Northern Luzon and Southern Mindanao.[437][438] The Philippine Independent Church is a notable independent Catholic denomination.[439][440][441]Iglesia ni Cristo is a notable Unitarian and Restorationist denomination in the country.[442][443]

Islam is the second largest religion. The Muslim population of the Philippines was reported as 5.57% of the total population according to census returns in 2010,[4] although a 2012 report by the National Commission on Muslim Filipinos estimates it at 11%.[444] The majority of Muslims live in the Bangsamoro region.[445][446][447][448] Most practice Sunni Islam under the Shafi’i school.[449][450]

An unknown number of Filipinos are irreligious, but they may form as much as 10% of the population.[451][452] Catholicism’s historic dominance is steadily declining, with about 9% of adherents considering leaving their church.[453]

An estimated 2% of the total population practice Philippine traditional religions, whose practices and folk beliefs are often syncretized with Christianity and Islam.[443][454] Buddhism is practiced by around 2% of the population, and is concentrated among Filipinos of Chinese descent.[443][449][454] The remaining population is divided between a number of religious groups, including Hindus, Jews, and Baha’is.[455]

Health